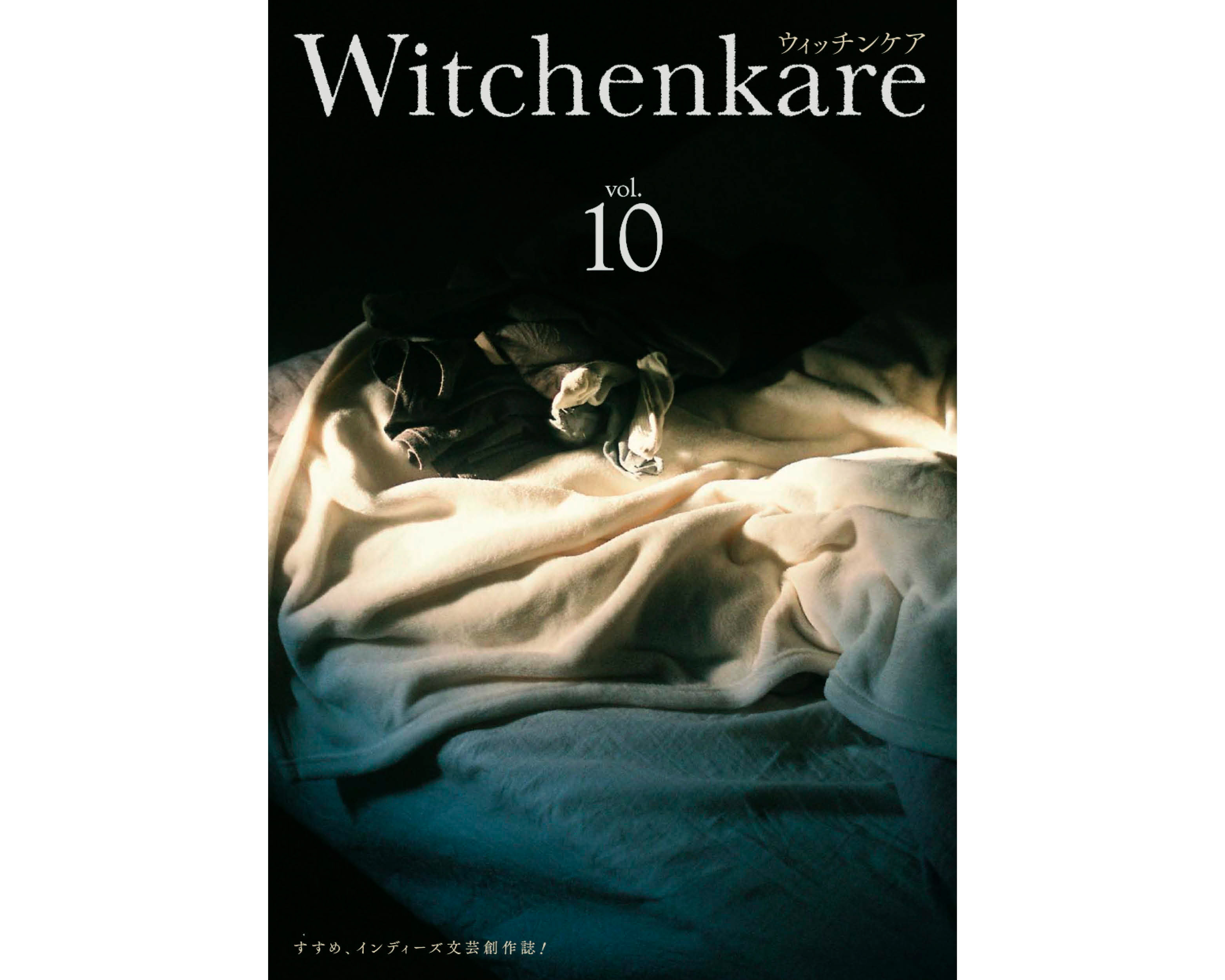

In the 2018 literary and creative magazine "Witchenkare", I wrote an essay titled "About Mr.Araki".

I wrote an essay about the photographer Nobuyoshi Araki.

I wrote an essay about the photographer Nobuyoshi Araki.

About Mr. Araki

There was a commercial complex called "Shinpukan" right next to Karasuma Oike in Kyoto. Originally an opulent brick building used as the Kyoto Central Telephone Office, it was renovated to include apparel brands and restaurants and opened in 2001. For a while, it had a strong presence as a trend-setting place in Kyoto, but the waves of the times drove it away and it ended its role in 2016.

As a university student in Shiga Prefecture at the time, I used to visit the Shinpukan whenever I went to Kyoto. There was no way that I, dressed in dirty clothes, would have any business in an apparel store, so I headed for the bookstore on the third floor. I used to spend the whole day browsing in the bookstore.

In the photo book corner of the bookstore, I casually picked up a photo book titled "Sentimental Journey: Winter Journey" by Nobuyoshi Araki, aka Araki. When I opened the red cloth cover, I saw a photo of a man with a beard and sunglasses and a woman in a wedding dress standing side by side in a hotel room, and on the next page, there was a handwritten sentence in red letters, "Zenryaku: I can't take it anymore," and the photos continued. As you read, you realize that this photo book is a story of love, life, and death between Nobuyoshi Araki, a photographer, and his wife Yoko.

The trajectory of the young couple's love, which began on their honeymoon, eventually came to an end with Yoko's death. I opened this photo book without any prior knowledge and read it to the end, crying inconsolably in front of the bookshelf. The more I tried to stop the tears, the more they came, and I was shaken by the love that flowed between the two people in the book, whom I had never met, and the determination of the photographer who continued to record it until the very end. It was the first time for me to cry over a photograph.

That was my first encounter with Mr. Araki as a photographer.

As a university student in Shiga Prefecture at the time, I used to visit the Shinpukan whenever I went to Kyoto. There was no way that I, dressed in dirty clothes, would have any business in an apparel store, so I headed for the bookstore on the third floor. I used to spend the whole day browsing in the bookstore.

In the photo book corner of the bookstore, I casually picked up a photo book titled "Sentimental Journey: Winter Journey" by Nobuyoshi Araki, aka Araki. When I opened the red cloth cover, I saw a photo of a man with a beard and sunglasses and a woman in a wedding dress standing side by side in a hotel room, and on the next page, there was a handwritten sentence in red letters, "Zenryaku: I can't take it anymore," and the photos continued. As you read, you realize that this photo book is a story of love, life, and death between Nobuyoshi Araki, a photographer, and his wife Yoko.

The trajectory of the young couple's love, which began on their honeymoon, eventually came to an end with Yoko's death. I opened this photo book without any prior knowledge and read it to the end, crying inconsolably in front of the bookshelf. The more I tried to stop the tears, the more they came, and I was shaken by the love that flowed between the two people in the book, whom I had never met, and the determination of the photographer who continued to record it until the very end. It was the first time for me to cry over a photograph.

That was my first encounter with Mr. Araki as a photographer.

Decades later, by a strange coincidence, I am now living as a photographer.

When I first became a photographer, I read and reread various photography books from all over the world. Among them, Mr. Araki's works and his eloquent theories on photography became my guiding light when I thought about what it means to take a picture, and I always had his words somewhere in my mind.

I was inspired to make my first self-financed photo book by Mr. Araki's "Xerox Photo Book," which he made at his own expense when he was a young Dentsu photographer.

In short, I learned about photography indirectly from Mr. Araki, and took the liberty of referring to his methodology as I built my own photographs.

It got to the point where I wanted to meet him someday, talk to him, and if possible, take a picture of him.

That opportunity came two years ago. I was asked to be the photographer to shoot Mr. Araki for a magazine project. In the two months leading up to the day of the photo shoot, I re-read his book and simulated in my mind over and over again what I was going to talk about while shooting. However, the day before the shoot, I received a call from the editorial department.

When I first became a photographer, I read and reread various photography books from all over the world. Among them, Mr. Araki's works and his eloquent theories on photography became my guiding light when I thought about what it means to take a picture, and I always had his words somewhere in my mind.

I was inspired to make my first self-financed photo book by Mr. Araki's "Xerox Photo Book," which he made at his own expense when he was a young Dentsu photographer.

In short, I learned about photography indirectly from Mr. Araki, and took the liberty of referring to his methodology as I built my own photographs.

It got to the point where I wanted to meet him someday, talk to him, and if possible, take a picture of him.

That opportunity came two years ago. I was asked to be the photographer to shoot Mr. Araki for a magazine project. In the two months leading up to the day of the photo shoot, I re-read his book and simulated in my mind over and over again what I was going to talk about while shooting. However, the day before the shoot, I received a call from the editorial department.

We got a call from the editorial department the day before the shoot: "Mr. Araki is not feeling well and cannot do the shoot. I'm sorry, but we'll have to sit this one out.

After hanging up the phone, I felt a sense of regret slowly seeping out of me, but at the same time, I was honestly a little relieved. At the same time, I was a little relieved. I decided to remind myself that we would definitely have another chance to meet.

The opportunity came again soon after.

Araki's work was exhibited at the Kyoto International Photography Festival held in Kyoto last year. Not only Mr. Araki's work, but also the works of other world-famous master photographers and up-and-coming photographers were exhibited at the festival, and my work was also selected for display.

The work was called "Falling Leaves," which depicted the lives of my 88-year-old grandmother and her 23-year-old cousin, a nursing student living in Miyazaki Prefecture.

I had been photographing these two people who had been living together for a long time, and I had planned to complete the work with the death of my grandmother, which was expected to occur in the not too distant future. However, this idea was overturned by an unexpected turn of events. One day, his cousin suddenly disappeared and disappeared. No matter how hard they searched, they could not find him. One year after his disappearance, he was found in the mountains. He had never returned. He had committed suicide.

My grandmother also passed away the following year with the shock and grief of her death.

With the two gone, all that was left were a number of photographs of them as they were in the past. I attempted to compile them into a story, hoping to leave traces of their lives.

It was a good attempt, but the process was quite painful. The two people in the photos were still alive today, moving and having a happy time. That's why I felt like my heart was being ripped out even more. It seemed impossible for me to create a work of art while maintaining an objective view of what had happened to my family, and there was no way I could figure out how to structure this story. I was at a loss to figure out how to compose this story. It had a different feel and weight than any other work I had ever made.

It was during this time that I pulled out a photo book of Mr. Araki's from the bookshelf in my room and looked at it repeatedly.

Perhaps I wanted to imagine the situation of Mr. Araki at the time, when he released his works that mixed love with his wife, life and death, and by overlapping myself with it, I wanted to get a hint as to what was the meaning of my releasing the photos of my grandmother and cousins to the world. More than that, I may have wanted to find out from Mr. Araki's words and actions how I would take on the criticism and condemnation that would follow the release of this work, which is a kind of taboo work about the death of a close relative, and how I would be prepared to take on such criticism and condemnation as a photographer.

Either way, I was in a state of confusion at the time. While I was lost, I was still looking for a ray of light, so I read not only his photo books, but also his books and videos of the time when he created those works.

In the book, Mr. Araki says, "This is for me.

After hanging up the phone, I felt a sense of regret slowly seeping out of me, but at the same time, I was honestly a little relieved. At the same time, I was a little relieved. I decided to remind myself that we would definitely have another chance to meet.

The opportunity came again soon after.

Araki's work was exhibited at the Kyoto International Photography Festival held in Kyoto last year. Not only Mr. Araki's work, but also the works of other world-famous master photographers and up-and-coming photographers were exhibited at the festival, and my work was also selected for display.

The work was called "Falling Leaves," which depicted the lives of my 88-year-old grandmother and her 23-year-old cousin, a nursing student living in Miyazaki Prefecture.

I had been photographing these two people who had been living together for a long time, and I had planned to complete the work with the death of my grandmother, which was expected to occur in the not too distant future. However, this idea was overturned by an unexpected turn of events. One day, his cousin suddenly disappeared and disappeared. No matter how hard they searched, they could not find him. One year after his disappearance, he was found in the mountains. He had never returned. He had committed suicide.

My grandmother also passed away the following year with the shock and grief of her death.

With the two gone, all that was left were a number of photographs of them as they were in the past. I attempted to compile them into a story, hoping to leave traces of their lives.

It was a good attempt, but the process was quite painful. The two people in the photos were still alive today, moving and having a happy time. That's why I felt like my heart was being ripped out even more. It seemed impossible for me to create a work of art while maintaining an objective view of what had happened to my family, and there was no way I could figure out how to structure this story. I was at a loss to figure out how to compose this story. It had a different feel and weight than any other work I had ever made.

It was during this time that I pulled out a photo book of Mr. Araki's from the bookshelf in my room and looked at it repeatedly.

Perhaps I wanted to imagine the situation of Mr. Araki at the time, when he released his works that mixed love with his wife, life and death, and by overlapping myself with it, I wanted to get a hint as to what was the meaning of my releasing the photos of my grandmother and cousins to the world. More than that, I may have wanted to find out from Mr. Araki's words and actions how I would take on the criticism and condemnation that would follow the release of this work, which is a kind of taboo work about the death of a close relative, and how I would be prepared to take on such criticism and condemnation as a photographer.

Either way, I was in a state of confusion at the time. While I was lost, I was still looking for a ray of light, so I read not only his photo books, but also his books and videos of the time when he created those works.

In the book, Mr. Araki says, "This is for me.

"This is for myself. After all, I'm the first reader.

At the time, Mr. Araki, who had just published his work, seemed to have received severe criticism. "They called it "inappropriate," "your wife's death is none of anyone's business," and "an irreverent photograph. However, Mr. Araki brushed off the criticism, saying, "It's for my own sake," and sublimated his love for his wife, Yoko, into a photographic work. Although he said.

"This is the end of the first round for me as a photographer, isn't it?

"This is the end of the first round for me as a photographer, isn't it?

This is the end of my first round as a photographer. This must have been accompanied by a great deal of pain and sorrow. I think this was the only way for the photographer, who kept looking at his beloved through his photographs, to express his love in the best possible way.

Yes, in the end I was not sure who I wanted to make this work for, and what kind of story I wanted to weave.

As I traveled in Mr. Araki's footsteps, the fog that had been hanging over my mind began to lift, little by little.

Yes, in the end I was not sure who I wanted to make this work for, and what kind of story I wanted to weave.

As I traveled in Mr. Araki's footsteps, the fog that had been hanging over my mind began to lift, little by little.

"No matter what anyone says, I will always make my work.

Then, with the help of various people and through trial and error, I managed to create a work of art, which was to be shown for the first time at the Kyoto International Photography Festival.

However, I did not meet Mr. Araki at the festival. After all, he could not come to Kyoto due to ill health.

However, reality is a strange thing, and the place where I exhibited was the "Shinpukan" where I first encountered Mr. Araki's works.

Seeing my work displayed there, now a bare concrete ruin, with so many people visiting and crying, overlapped with the scene where I cried over Mr. Araki's photo collection more than ten years ago, and I felt a strange sense of fate. I would like to go talk to Mr. Araki about this someday.

However, I did not meet Mr. Araki at the festival. After all, he could not come to Kyoto due to ill health.

However, reality is a strange thing, and the place where I exhibited was the "Shinpukan" where I first encountered Mr. Araki's works.

Seeing my work displayed there, now a bare concrete ruin, with so many people visiting and crying, overlapped with the scene where I cried over Mr. Araki's photo collection more than ten years ago, and I felt a strange sense of fate. I would like to go talk to Mr. Araki about this someday.